UPDATE: Jeff Hawkins has a new book titled A Thousand Brains. The book details how The Thousand Brains Theory will impact the future of machine intelligence and what an understanding of the brain says about the threats and opportunities facing humanity. Visit AThousandBrains.com for more information.

First posted in March 2018; updated in January 2019

In our most recent peer-reviewed paper, A Framework for Intelligence and Cortical Function Based on Grid Cells in the Neocortex, we put forward a novel theory for how the neocortex works. The Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence proposes that rather than learning one model of an object (or concept), the brain builds many models of each object. Each model is built using different inputs, whether from slightly different parts of the sensor (such as different fingers on your hand) or from different sensors altogether (eyes vs. skin). The models vote together to reach a consensus on what they are sensing, and the consensus vote is what we perceive. It’s as if your brain is actually thousands of brains working simultaneously.

A key insight of our theory is based on an understanding of grid cells, neurons which are found in an older part of the brain responsible for navigation and knowing where you are in the world. Scientists have made great progress over the past few decades in understanding that the function of grid cells is to represent the location of a body in an environment. Recent experimental evidence suggests that grid cells also are present in the neocortex. We propose that grid cells exist throughout the neocortex, in every region and in every cortical column, and that they define a location-based framework for how the neocortex works. The same grid cell-based mechanism used in the older part of the brain to learn the structure of environments is used by the neocortex to learn the structure of objects, not only what they are, but also how they behave.

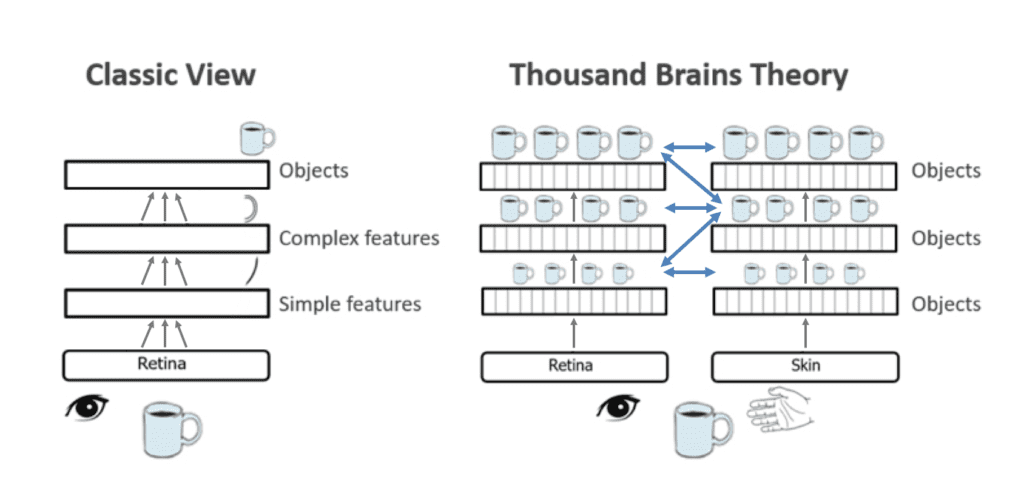

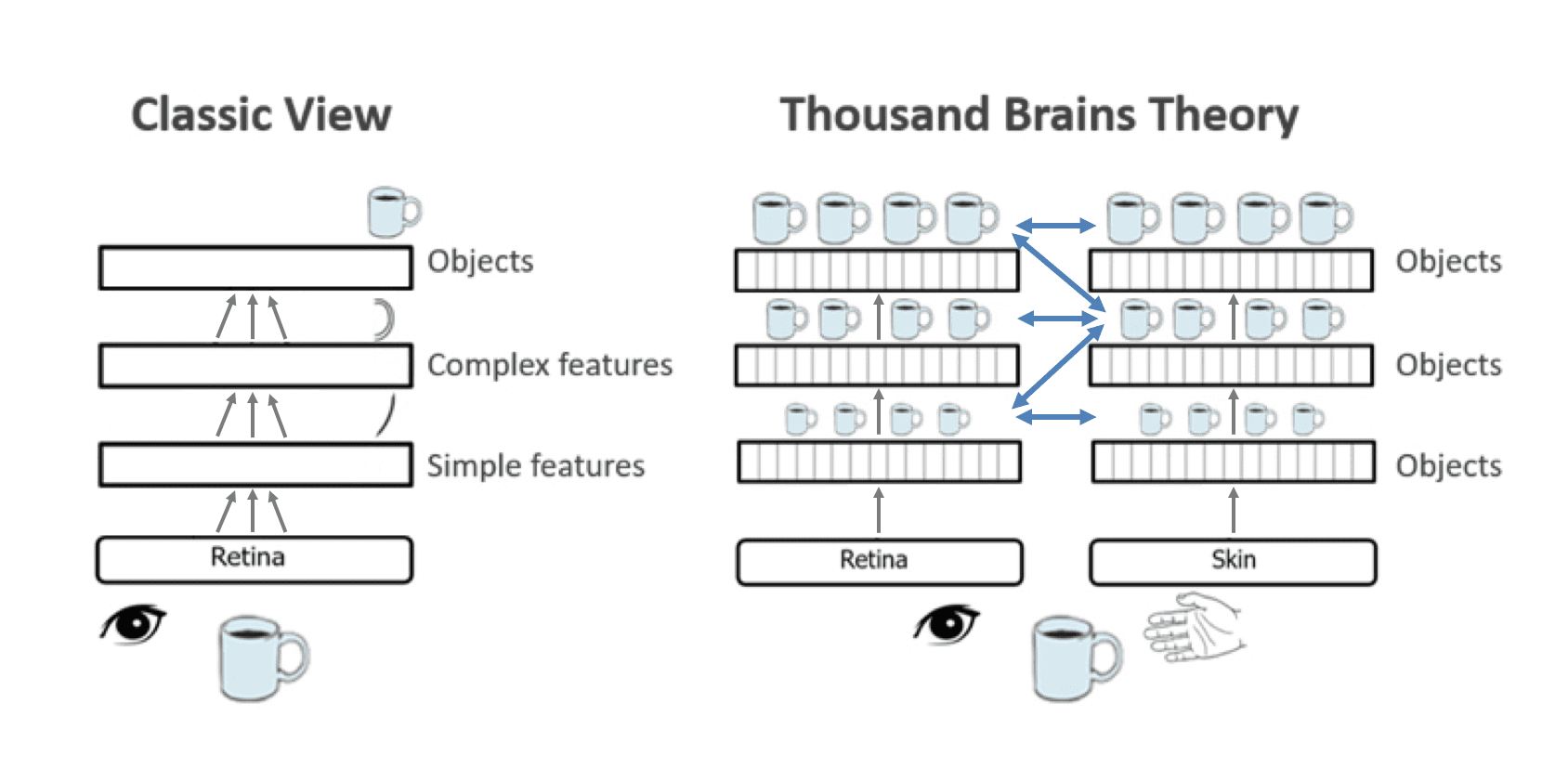

The Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence is very different than current neural networks. Most neural networks are based on a long-standing view that the neocortex receives input from a sensory organ and processes it in a series of hierarchical steps. Sensory input ascends from region to region, and at each level, cells respond to larger areas and more complex features of a sensory array. It’s commonly assumed that complete objects can only be recognized at a high enough level in the hierarchy where cells can take in the entire sensory array.

In the Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence, each column creates complete models of its world, based on what it can sense as its associated sensor moves. Columns combine sensory input with a grid cell-derived location, and then integrate those “sensory features at locations” over movements. Long-range connections in the cortex allow columns to work together to quickly identify objects.

To illustrate this concept in our newest paper, we use the example of a coffee cup. Imagine touching a coffee cup with one finger. As you move your finger over the cup, you sense different parts of it. You might feel the lip, then the curve of the handle, then the flatness of the bottom. Each sensation you receive is processed relative to its location on the cup. The curved handle of the mug is always in the same relative position on the cup; it is not a feature relative to you. At one moment it might be on your left and another moment on your right, but it is always in the same location on the cup. If you were asked to reach into a box and identify this object by touching it with one finger, you probably couldn’t with a single touch. But if you continued to move your finger over the object, you would integrate more sensory features from different locations, until you recognized with certainty that the only object containing this set of features at these locations is the coffee cup.

Now imagine the same mug, but this time you grasp it with multiple fingers at the same time. Whereas before you had to move your finger to recognize the cup, now you might be able to recognize it with a single grasp. The columns associated with each finger don’t have enough information on their own to identify the cup, but connections between columns allow them to reach the correct answer more quickly. In effect, the columns “vote” as to what is the most likely object, and quickly settle on cup. The same process occurs across senses, so cortical columns that process visual input can communicate with columns processing touch. In fact, there are connections in the cortex between low level sensory regions that don’t make sense in the classic hierarchical model of the cortex but do make sense in the Thousand Brains Theory.

So, an individual column can recognize objects through movement (one finger touching the mug multiple times) or through long-range connections between columns that share information to agree on what the object is (grasping and looking at a mug). Here is a cartoon illustration showing the classic hierarchy and our proposed alternate model. Notice that we are not suggesting that the cortex is not organized as a hierarchy of regions; it is, and the hierarchy is important. But complete models of objects exist at each level of the hierarchy.

Implications for AI

If brains are organized this way, then it raises the question: do we also need to build intelligent machines this way? Today’s artificial neural networks work on the classic hierarchical view, often with one hundred or more levels. These networks are very good at classifying images and other patterns. So, it might appear that the Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence is not required for AI. However, it is widely believed that today’s AI is not close to the flexibility of human intelligence, and it is not nearly as capable in applying learning in one domain to different types of problems, a.k.a. generalization.

There are two reasons to suggest that the Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence is required to solve these and other challenges. First, our proposal says that columns in the cortex learn the three-dimensional shape of objects, not just a two-dimensional shape that appears on our sensors. This more robust object model provides a basis for learning the behaviors of objects, or how the shape and appearance of an object changes over time when we interact with it. A three-dimensional representation of objects also provides the basis for learning compositional structure, i.e. how objects are composed of other objects arranged in particular ways. In our paper, we provide details on the mechanisms for how the cortex represents object compositionality, object behaviors and even high-level concepts. Second, the Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence provides a means for integration across sensory modalities, what is sometimes called “sensor fusion.” It provides a model for how learning in one modality, such as touch, can be applied to and integrated with other modalities, such as vision.

The Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence is a rich concept that allows us to explain many mysteries of the brain. We are optimistic that this work provides fresh insight that can be applied to build more intelligent and useful AI products.

If you’re interested in learning more about the details behind the Thousand Brains Theory of Intelligence, here are some additional resources:

- A Framework for Intelligence and Cortical Function Based on Grid Cells in the Neocortex (2019)

- For those who want a less detailed overview of the theory:

- For those who want more details, including network models on core components of the theory: