Admit it, you’ve been ignoring the thalamus, haven’t you? Turns out you’re not alone. Even many neuroscientists have a very simplistic notion of thalamic function and tend to ignore it. As a result, although there has been significant computational work on various aspects of the neocortex, there are almost no computational models of the thalamus. Fortunately, that may be changing. Over the last few decades scientists have discovered a wealth of information about this oft-neglected region of the brain. In this post I’ll give you an overview of the thalamus and these findings. The details are fascinating, and have been impacting Numenta’s theories of cortical function. Perhaps most important, I’m going to try and convince you that the thalamus is not only an integral part of the neocortex, but of intelligent function in general.

What is the thalamus?

The thalamus is a nutshell shaped region of the brain that sits in the very center of your skull, as shown in red in the animation on the right[1]. The central location of the thalamus is a clue to its function. It turns out that almost all sensory information coming into the neocortex flows through the thalamus.

The thalamus is a nutshell shaped region of the brain that sits in the very center of your skull, as shown in red in the animation on the right[1]. The central location of the thalamus is a clue to its function. It turns out that almost all sensory information coming into the neocortex flows through the thalamus.

The thalamus is not a single homogeneous structure – it is actually composed of dozens of groups of cells, called nuclei. Each nucleus has a complicated name, like “lateral geniculate nucleus” (LGN), and “the dorsal medial geniculate body” (dMGB). If you want to impress someone at a party, those are the terms to throw around! Each nucleus is responsible for relaying some of the information going into a specific cortical region. Indeed, throughout the last century in neuroscience, the prevailing notion has been that the thalamus is nothing more than a “relay station to the neocortex”. This simplistic view has actually caused people to ignore it, under the assumption that there is nothing really interesting going on.

The thalamus: much more than a relay

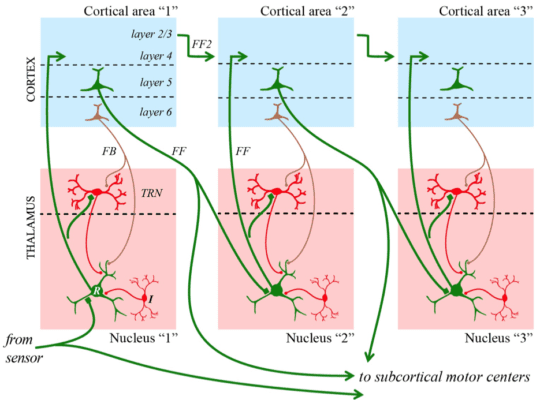

Recent evidence suggests that the role of the thalamus is actually far more important. It turns out that each region of the neocortex weaves an intricate, but regular, web of connections back and forth with a particular nucleus[2], as shown in the following figure (adapted from (Sherman, 2018b)).

The diagram shows the physical connectivity between the neocortex and the thalamus. The upper row shows different cortical regions, and the lower row shows the thalamic nucleus associated with each region. In the box below I’ve listed out many of the interesting details, some of which get pretty technical, but you can immediately see that there is a fairly sophisticated pattern. The most important fact is that this is a canonical pattern in the sense that it is preserved in all cortical areas and nuclei, regardless of modality.

There are two broad conclusions we can draw. First, it should be obvious from the complexity that the thalamus is not just a relay station. There is a lot more going on. Second, the fact that each nucleus is tightly coupled to a cortical region and that the anatomy is consistent everywhere imply that it is an integral component of the common cortical circuitry. The thalamus is not just some independent brain region. You must understand the thalamus if you want to understand the common cortical algorithm.

Some detailed aspects of cortico-thalamic connections:

- Each cortical region sends a strong feed forward projection from Layer 5 to the next thalamic nucleus that then projects to Layer 4 of the next cortical region (arrows labeled “FF”). This indirect projection is in addition to the direct projection from Layer 2/3 to Layer 4 of the next region (“FF2”). Thus there are two feedforward pathways from one cortical area to the next. Sherman and Guillery have shown that the indirect thalamic pathway is actually the stronger one[2].

- The projection from Layer 5 splits off and also projects to subcortical areas responsible for controlling our motor/muscle systems and behavior. This projection, known as an “efference copy”, is thought to modulate behavior but also simultaneously sends information to the next cortical area. The nature of this signal is a mystery.

- There are reciprocal feedback connections from each cortical region to the same thalamic nucleus that projected to it. These are labeled “FB” in the diagram and originate in Layer 6. They pass through a sub-layer of the thalamus called the TRN (or the “thalamic reticular nucleus”, another wonderful party word). More on the TRN later.

- The anatomy within the thalamus itself is fairly sophisticated. The cells within the thalamus and their dendrites are quite specialized, and have complex dynamic properties[2].

- The connectivity pattern outlined above is canonical and applies to all cortical areas and nuclei, regardless of modality. It applies to vision (associated thalamic nuclei: LGN, pulvinar), to audition (thalamic nuclei: dorsal and medial geniculate bodies), touch (thalamic nuclei: ventral posterior, posterior medial), motor cortices (thalamic nuclei: ventral anterior and ventral lateral) and even high order cortical areas (thalamic nuclei: medial dorsal, midline nuclei).

The thalamus: what is it doing?

If the thalamus is not just a relay, what is it doing exactly? Unfortunately, as I mentioned earlier, there are almost no computational theories of the thalamus. Perhaps the most common theory is that it is responsible for controlling attention. First proposed by Francis Crick[3], there is growing evidence for this hypothesis. Crick noted that the TRN, the layer of inhibitory cells surrounding thalamic nuclei, is perfectly suited for attentional control. It receives input from cortex and could thus inhibit or modulate activity to specific sensory areas based on directions from cortex. Recent experiments have provided some support for this hypothesis[4],[5],[6].

This is exciting, but unlikely to be the complete story. The feedback projections are approximately 10X larger in number than the feedforward projections. The anatomy is far more complex than what is required for attention, and the thalamus can in principle do much more than restrict attention to a sensory region. A recent review by Rikhye et al.[7] considers this question and mentions a few other possibilities, including the idea that the thalamus might perform contextual, task-specific computations.

We also know that the thalamus is critically involved in sleep cycles. In particular it is thought to be responsible for generating a particular type of neural activity, known as spindle waves, during our non-REM sleep cycles. Sleep is required for memory consolidation, and the thalamus may be an important component of this process.

In general though, theoretical ideas are sparse. At Numenta we are working to understand the role of the thalamus better. Within neuroscience, more modeling and experimentation are required to improve our understanding of this core component of the common cortical microcircuit. Until we do, we are unlikely to fully understand intelligent computation in the brain.

The thalamus: how does it impact our theories?

At Numenta our research is focused on understanding the common cortical microcircuitry. In this blog post I’ve argued that the thalamus is an inextricable component of this circuitry. Logically, it follows that our theory has to incorporate the thalamus! Jeff Hawkins recently wrote about one aspect of this, the second feedforward pathway through the thalamus[9]. This pathway is mysterious, and its functional role in our model is an active topic of discussion in our lab meetings. We also know that we have to incorporate attention into our model, but have not done so yet. Overall, we acknowledge that the thalamus is a key part of the common cortical algorithm and are working actively on incorporating it into our framework.

Where to go to learn more

In this post I’ve only scratched the surface and made a bunch of simplifications (thalamic researchers must be squirming in their seats). Below are links to the papers referenced above. If you’d like to understand a little bit more, the YouTube video titled “[The Thalamus][10]” by Brains Explained is an excellent 10 minute introduction to the thalamus[10]. For those who want more detail, Prof. Murray Sherman delivered an excellent pair of lectures earlier this year that dive into thalamic anatomy and function[11],[12].

References

1. Thalamus animation from wikipedia: [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thalamus]

2. Sherman, S.M. & Guillery, R.W. (2013) [Functional Connections of Cortical Areas: A New View from the Thalamus]. The MIT Press.

3. Crick, F. (1984) [Function of the thalamic reticular complex: the searchlight hypothesis]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 81, 4586–4590.

4. Halassa, M.M., Chen, Z., Wimmer, R.D., Brunetti, P.M., Zhao, S., Zikopoulos, B., Wang, F., Brown, E.N., & Wilson, M.A. (2014) [State-dependent architecture of thalamic reticular subnetworks.] Cell, 158, 808–821.

5. McAlonan, K., Cavanaugh, J., & Wurtz, R.H. (2008) [Guarding the gateway to cortex with attention in visual thalamus]. Nature, 456, 391–394.

6. Ortuno, T., Grieve, K.L., Cao, R., Cudeiro, J., & Rivadulla, C. (2014) [Bursting thalamic responses in awake monkey contribute to visual detection and are modulated by corticofugal feedback]. Front. Behav. Neurosci., 8, 1–10.

7. Rikhye, R. V, Wimmer, R.D., & Halassa, M.M. (2018) [Toward an Integrative Theory of Thalamic Function]. Annu. Rev. Neurosci., 163–183.

8. Sherman, S.M. (2006), Scholarpedia, 1(9):1583. [http://scholarpedia.org/article/Thalamus]

9. Hawkins, J. (2018) [Two paths diverged in the brain, Ray Guillery chose the one less studied]. Eur J. Neuroscience.

10. The Thalamus (2017), Youtube video by Brains Explained. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fki7AmLma_I]

11. Sherman, S.M.(2018a). Thalamocortical System I. Lecture at the Simons Institute, Berkeley. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aB2M1gg_1sU]

12. Sherman, S.M.(2018b). Thalamocortical System II. Lecture at the Simons Institute, Berkeley. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBILhSTpzFI]