As usual, in early March a bunch of us (Jeff, Subutai, Scott, Marcus, and Mirko) attended the Cosyne conference. (This was the fourth Cosyne attended by Numenta.) This annual academic conference is an excellent forum to interact with experimental and theoretical neuroscientists from around the world. There were roughly 750 attendees this year, a little larger than past years. The main conference is composed of single track talks followed by poster sessions. Everyone then heads off to the mountains for two days of focused workshops and skiing.

The sessions start early in the morning and end late at night; this goes on for six days. The conference is super intense and tiring, but overall Cosyne is the best way to get an in-depth understanding of the latest research in Computational Neuroscience.

Our participation

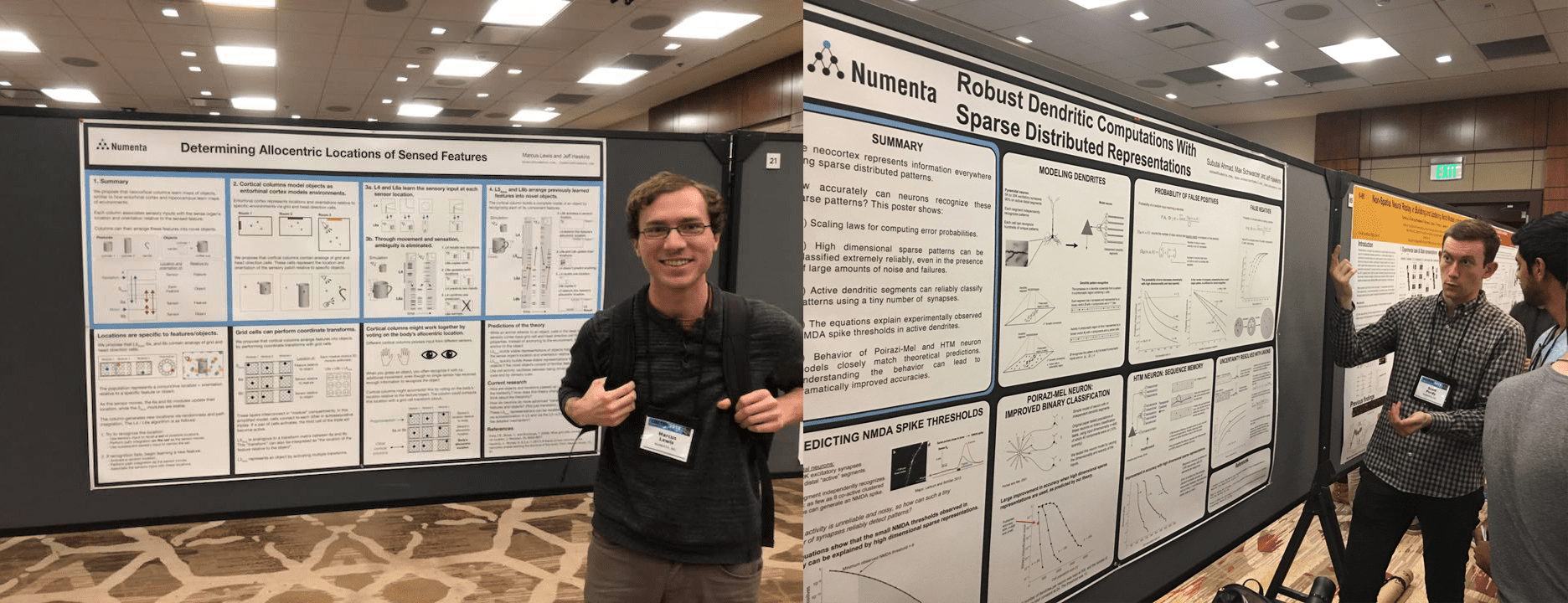

This year, Numenta had 2 posters and one workshop talk at Cosyne:

Marcus Lewis and Jeff Hawkins presented our latest thinking on object modeling in cortical columns. Specifically, they discussed how the neocortex might model objects using the same mechanisms the hippocampal formation uses to model environments. The work builds on the Columns paper we published last year. Marcus had a great series of tweets that described the details of the poster, “Determining Allocentric Locations of Sensed Features.”

Subutai Ahmad and Scott Purdy presented a poster, “Robust Dendritic Computations With Sparse Distributed Representations”, that discussed a mathematical model of sparse distributed representations (SDRs). The math shows that high dimensional sparse patterns can be classified extremely reliably, even in the presence of large amounts of noise and failures. The equations explain experimentally observed NMDA spike thresholds in active dendrites, and solve the mystery of how a tiny number of synapses (20-30) can reliably detect complex patterns buried within large populations of neurons.

It was great to be able to present two posters, as they represented two different phases of Numenta research. While the first poster was on a relatively new research topic, the second was on a topic that has been at the core of our theory for nearly a decade! It was encouraging to see good reception for both, and we hope this is indicative of the longevity of our work.

Subutai also gave a talk at the workshop on “Cortical circuits: functions and models of long-range connections.” He presented our models of dendrites, sequence and object learning in cortical columns, and how that impacts how we think about long-range connections in the neocortex.

With three presentations, it was a busy Cosyne for us. As always, discussing our work led to several interesting in-depth discussions with neuroscientists. We returned to Numenta with new ideas and perspectives.

Interesting trends

Several topics were covered in depth this year. There were many talks and posters that explored the properties of grid cells, such as a talk on Sunday by Malcolm Campbell. A lot of work was dedicated to understanding decision making and building reinforcement learning models. Oscillations were a popular topic, especially in the context of working memory, which had it own workshop session. And recording techniques continue to improve, resulting in new experiments using technologies such as Neuropixels.

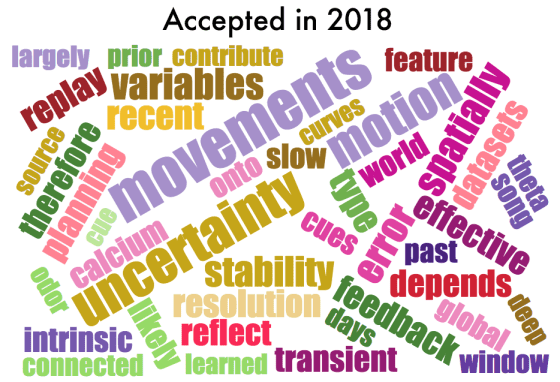

Adam Calhoun has a nice blog, where he analytically summarizes some of the interesting trends at Cosyne. As an example, his word cloud of accepted abstracts clearly shows that movement and behavior were fairly important this year:

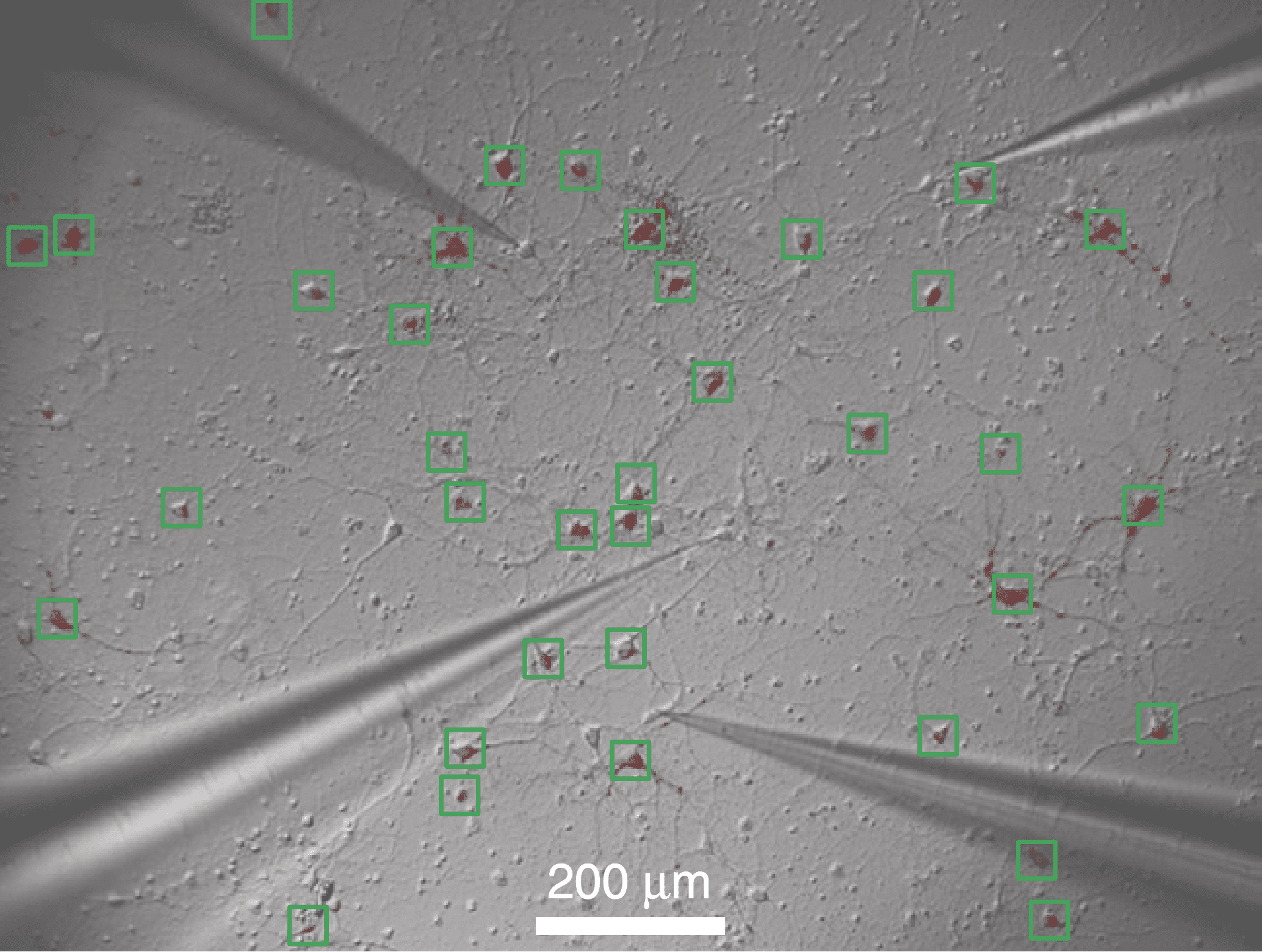

Most creative experimental technique

Jeremie Barral presented a workshop talk about results from an experiment with an interesting setup. He uses a technique for separating neurons out of a small slice of cortex, so that they can be optogenetically stimulated and recorded from a constrained glia-free culture. The picture above, taken from his 2016 Nature Neuroscience paper, shows one such culture with some neurons stained red and highlighted with green boxes. Four recording probes are also visible. With this technique, the connectivity can be restricted, and every cell in the network can be targeted for optical stimulation. Typical recordings and slice preparations are stuck with the structure and connectivity already present in the tissue. This technique enables complete control of the structure of the neuronal network and the times at which each neuron receives direct activation. The technique could be useful for studying plasticity and the balance between excitatory and inhibitory activations. You can read more about the technique here.

Other talks and posters

We enjoyed the invited talk by Tim Behrens from Oxford, where he approaches the question of how mammals navigate abstract conceptual spaces. He emphasized the importance of a code that represents the relationship between two abstract instances and organizes it in a graph like structure that can be flexibly queried. He proposes that grid-cell like neurons in cortex are involved in navigating these spaces, and showed some evidence for this. There are many analogies to our proposals that cortical columns use grid cells to represent locations and relationships between features.

Our Columns paper proposes that cortical columns can learn to model complete objects. Our model makes several predictions about the behavior of the upper layers (layers 2/3) in the presence of ambiguous input. A poster by He Zheng and Hyung-Bae Kwon from the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience looked at responses in Layers 2 and 3 when an animal had been raised in an impoverished environment vs an enriched environment with a lot of objects. As predicted by our model, stimulating a single ambiguous input led to denser activity in the upper layers for the animals raised in enriched environments. In our model, this is an indication of greater uncertainty when a larger number of objects are possible. It was nice to see this prediction supported experimentally.

Joshua Berke from UCSF gave an interesting talk titled “What does dopamine mean?”. Dopamine is a neuromodulator that is heavily linked with reinforcement learning in the brain and overall motivation levels. Berke gave a nice review and introduction to the Dopamine system. He then argued that levels of dopamine encode a predicted value of a reward. He claimed this matches experimental results better than other explanations. Moreover, from this signal you can easily calculate reward prediction error, which is the actual quantity used to train reinforcement learning models.

Mirko adds, “I enjoyed Sam Gershman’s talk about model-based reinforcement learning. The question he approaches arises around the question of how that model should be structured. In his talk, he illustrates the importance by comparing the learning curves of Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and humans playing the Atari game of Frostbite. While DQN outperforms humans eventually, it is crucial to notice that the learning curve of humans is incredibly steeper than the DQN’s, which suggests that both perform a very different kind of learning.”

Overall, with these talks, posters, and meetings, plus our three presentations it was a busy but rewarding week. We’re already looking forward to next year’s March Madness with Cosyne 2019.